- Home

- Toni Morrison

Mouth Full of Blood Page 10

Mouth Full of Blood Read online

Page 10

Among modern feminists this first split quickly gave way to a second from which two main groups emerged: socialist feminists, who blame capitalism for the virulence of sexual oppression, and radical feminists, who blame men. The outrage of both socialist and radical feminism is directed toward the cause of sexism, yet in pursuit of the enemy, much of the emotional violence spills over to the victims. Regardless of how they define the enemy (men or the “system”) both camps recognize the need to neutralize the hostility of women toward one another—sisters, mothers, and daughters, women friends and employees. They see betrayal among women as a residue of minority self-contempt and the competitiveness of the marriage market. Nevertheless, the result of a raised consciousness in the company of a repressed one is frequently an explosive internecine conflict. There is stark terror in Andrea Dworkin’s account of her attempts to talk to right-to-life women in Houston. There is real arsenic in Simone de Beauvoir’s recollection of her rivalry with her mother. Even among advanced feminists sabotage is a serious threat. A nice little feminist collective bookstore in California (called Woman’s Place) ended up in court when the separatists locked the integrationists out.

The anti-feminists, who have the greatest support of men, are presumed by feminists to be endlessly gestating and lactating; happy for any system, political, economic, or cultural, that manages men and keeps them if not responsible, then certainly at bay. Blaming feminists’ communism, and atheism, anti-feminists are convinced that the male role as providers and fathers is the apex of civilized society. It does not trouble them that finding a role for men, other than fathers or husbands, is still a serious problem for anthropology. That while “nature” easily defines a woman’s role, “society” must provide a definition of male roles. Trying to figure out what—other than fathering and providing for children—men are for leads the researcher into an investigation of “civilization” and male-dominated positions within it. Since fatherhood is not fulfilling enough for men, they see themselves as doers, leaders, and inventors, and it does not take a major intellect to see that women, free of home and child care, may be expected to do, lead, and invent as well. Contemplating such a radical change in expectations can range from uneasiness to terror. Anti-feminists are not categorically opposed to male-like activities for women, but they regard them as either secondary freedoms or not freedoms at all, but rather as heavy requirements that will deprive them of a hard-won protectionism. Thus their disgust with ERA, abortion on demand, and a host of other feminist goals.

The agnostics, or nonaligned humanists, are probably the largest of all three groups and, although courted by feminists and anti-feminists alike to swell their numbers, they have earned the contempt and mistrust of both. Feminists regard them as scabs and opportunists, benefiting from feminist work while contributing nothing to it—even scorning it. They are the women in academia who accept their tenured positions as part of the fruit of feminist labor, who identify themselves as representing womanpower, but who are quick to disassociate themselves from “merely” feminist scholarship (“I teach Milton”). Anti-feminists see them as cowards and profiteers benefiting from protectionism when it suits them but flagrantly chucking it when it does not. They are the dissatisfied wives making feminist claims about house and child care and sexual freedom without parallel claims of responsibility. All of their energy is channeled into the competitive ethos of physical beauty. They decorate and market themselves in precisely the manner of a 1950 pinup; mutter about the hopelessness of men, but regard themselves and other women as incomplete without a male liaison. Nonaligned women are embarrassed by the extravagant or aggressive behavior of radical feminists and dismiss them as unattractive, male-minded Amazons. Equally contemptible to them are the anti-feminists, whose oratory amuses them and whom they see as ignorant, religious fanatics, or simply slavish. The “reasonable” neutrality of the nonaligned humanist is viewed as quisling by the converts of the right or left.

Among these three groups, the field for battle is wide and loaded with weaponry. Sad as these divisions are, they exist because of genuine concerns—serious unresolved questions about biology and bigotry.

The biological bind, whether blessing or curse, is real. Whatever the disposition of women today (radical, anti-, or nonaligned) they are forced relentlessly into selling or trading on their vaginas or their wombs. As “involuntary” mothers, trading on the womb means demanding protection as a class for the product that organ can manufacture—children. For “voluntary” mothers, the womb becomes the nexus for demanding the right to terminate its activity. As mistresses, prostitutes, housebound wives, and pornographic “actresses,” women are involved in the dollar value of their vaginas and must come to terms with accepting that value as the way the world is and ought to be, or the way it is but ought not to be. Because a woman’s livelihood has always been connected to her sexuality, whether maiden, mistress, wife, or prostitute, fidelity is women’s work—not men’s. “Relating to men in bed and in marriage is the conventional passport to normal femininity.” And it is incumbent upon the woman to advertise her faithfulness and maintain his. It is this burden of fidelity, coupled with the economics of sexuality, that puts heterosexual women in direct conflict with lesbians.

Homosexual, or women-identified women, struggling to eliminate males and their domination from their personal and sexual lives, are convinced that lesbianism is the only way to achieve the full potential of women. Many look forward to a world that they envision as completely genderless, although it is not immediately clear where future lesbians will come from without some contact with men or, at the least, their bottled sperm. For the moment their position requires sharing with male scientists the lively optimism that fuck-free childbirth methods have encouraged. Yet female homosexuals are not alone in these dreams of a peaceable genderless kingdom, as the growing number of women writing science fiction is proof of. So problematic is the gender barricade, many feminist writers have turned to science fiction in order to invent a transcendent universe—free of the limitations of biology.

The second concern that generates divisiveness among women is the tenacity of male bigotry and its grave effect on the lives of all women regardless of what camp they belong to. Men still determine the scientific, political, and labor goals of this society. Scientific manipulation in areas of reproduction has turned out to be a very mixed blessing. It was a woman, Margaret Sanger, who had the idea and raised the money for a man, Dr. Pincus, to develop a “simple, cheap, safe contraceptive to be used in poverty-stricken slums, jungles, and among the most ignorant people.” The specificity of the assignment was important and decisive, proving that the suspicions of minority women about all birth control campaigns are well-founded. Notwithstanding the original intention, “the pill” has been identified as the principal liberating factor for women of all colors since 1960. Yet the dramatic decline in infant births and mortality from pregnancy is outweighed by the staggering increase in reproductive death due to birth-control devices. The contraceptive that stops birth also kills women, but because the class and race implications in birth-control campaigns are systemic, there is no guarantee that the danger will decrease even if women do finally control fertility among themselves and their sisters in the jungle. The picture of wave upon wave of nonwhite babies growing into vocal hungry adulthood is routinely evoked by feminists trying to persuade others to their point of view.

In spite of some progressive legislation and increasing numbers of women in politics, and in spite of the percentage of registered women voters, no one questions the fact that politics is by men and for men. No one even bothers to wonder why so many women in politics are conservative. The eagerness for political heroines is so keen that apologies for reactionary women leaders can be safely left to the left. But these apologies do not hide the fury between left-wing women and their right-wing sisters. Witness any issue-oriented platform, such as those involving school desegregation, abortion rights, prayer in schools, and so on.

> The control men exert on the labor market is exacting—more so now because house-free women are clearly superfluous to laissez-faire or corporate capitalism. There is too little work and too much skill. Too little work and too many workers. Teens, minorities, women, recently retired people, farmers, factory workers, and the work-trained disabled are the reserve workforce available for constantly changing labor needs. And built into this supply-demand system is a violent job-career struggle that seethes in offices and factories everywhere. Because of their dependency, women are the most disposable of laborers.

Biology and bigotry are the historical enemies—the ones women have long understood as the target if sexism is to be uprooted. What is newer and perhaps more sinister is the growth of the female saboteur, who seems to be crippling the movement as a whole: the internecine conflicts, cul-de-sacs, and mini-causes that have shredded the movement, steered it away from the serious political revolution of its origins, and trivialized it almost beyond recognition. Why have right-to-life and abortion-on-demand issues made women their own antagonists? Why do prostitutes regard women fighting pornography as uselessly obstructionist? Why are black and other minority women so quick to freeze out white feminist leadership? Why are women, for all our public talk of solidarity, firing our assistants because and when they are pregnant, voting against the appointment of women deans and chairpersons, relating to maids as though they were property, turning over buses on other mothers’ black children? While these skirmishes continue, the movement comes dangerously close to an implosion of women-hating-women at worst, or a defeated disarray of cul-de-sac and mini-causes at best—all demonstrating the basest of male expectations: that any organization of women would end in a hair-pulling contest, as entertaining and irrelevant as those lady mud wrestlers.

How can a dignified, responsible women’s liberation revive itself and proceed without shaming itself into women’s lamentation? Perhaps if we listen closely to the ferocity, the eloquence, the pleas devoted to the cause of women, we will hear another message—one that informs the lament: that masculinity or male likeness is, after all, a superior idea. That all the way from radical feminists who believe men are less suited for masculinity than anybody, to “total” women, who believe men are simply better, the concept of masculinity still connotes adventure, integrity, intellect, freedom, and, most of all, power. “Man is the measure of man” is an easily dismissed observation in a modern context, but masculinity is very much the measure of adulthood (personhood). Proof is everywhere. It shapes the wishes of women who believe they are born to please men as well as those who want to have what males claim for themselves. It ignites the drive of women who wish to be thought of as competent, brilliant, tough, thorough, just, and reasonable. Rigorous intellect, commonly thought of as a male preserve, has never been confined to men—but it has always been regarded as a masculine trait. Relinquishing reproductive control to God is, in fact, relinquishing it to men. Demanding reproductive control is to usurp male sovereignty and acquire what masculinity takes for granted—dominion.

Rather than limit the definition of feminine to one chromosome, rather than change the definition to elevate the other chromosome, why not expand the definition to absorb both? We have both. Not wanting or needing children should not mean we must abandon a predilection for nurturing. Why not employ it to give feminism a new meaning—one that distinguishes it from woman-worship and from man-awe? The truth is that males are not a superior gender; nor are females a superior gender. Masculinity, however, as a concept, is envied by both sexes. The problem, therefore, is this: the tacit agreement that masculinity is preferable is also a tacit acceptance of male supremacy, whether the “males” are men, male-minded women, or male-dominated women, and male supremacy cannot exist without its genitalia. Each sexist culture has its own socio-genital formation, and in the United States the formation is racism and the hierarchy of class. When both are severed, male supremacy collapses and the sea of contention among women will dry up.

Pretending that racist elements in male supremacy are secondary to sexism is to avoid, once again, the opportunity to eradicate sexism completely. Just as it was avoided by nineteenth-century abolitionists, so it has been ignored in twentieth-century feminism. The persistent refusal to confront it not only supports male supremacy, it creates battle lines with forty million women on one side and sixty million on the other.

Accepting male-defined, male-blessed class hierarchy is also to strangle the movement and keep us locked in a fruitless war in which each of us is a female saboteur.

Complicity in the subjugation of race and class accounts for much of the self-sabotage women are prey to, for it is straight out of that subjugation that certain female-destroying myths have come. One is the myth of the malevolent matriarch, a myth so prevalent that Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s conclusions about matriarchy as a cause of pathology among blacks is echoed in the literature of black men and women as well as white. This, in spite of the fact that only 16 percent of all households report males as the sole providers (governments insist a household have a “head” and are alarmed when it is not a man). Nothing in black life supports the thesis of black men as “feminized” by their women and everything points to white male suppression as the emasculating force. Yet this distortion is thriving like health. Italians, Jews, Hispanics, WASPs—all have had their social problems explained in part by their success or failure in taming a threatening matriarch.

Another female-destroying myth is the classlessness of laissez-faire capitalism and socialism. In advanced capitalism women have no economic autonomy and are dependent on the “uncertain male-determined fortunes as wives, mothers, and housekeepers.” In Marxist societies, where classes are identified according to their relation to production, the family unit with its internal stratification (man equals head) defies any attempt to describe adequately the production of the “unwaged”—that is, the housewife.

Class stratification sharpens and politicizes the fight for goods and status. Along with all the other conflicts it generates, class inequality exacerbates the differences between black and white women, poor and rich women, old and young women, single welfare mothers and single employed mothers. It pits women against one another in male-invented differences of opinion—differences that determine who shall work, who shall be well educated, who controls the womb and/or the vagina; who goes to jail; who lives where.

The willingness of innocent, ignorant, or self-regarding women to dismiss the implications of class prejudice, and to play roles that act in concert with the male-defined interests of the state, produces and perpetuates reactionary politics—a slow and subtle form of sororicide.

There is no one to save us from that—no one except ourselves. So in the debris of what once looked like a vital liberation movement, one searches for signs of life. Three beacons wink in the wasteland. The dogged and often thankless work being done by fewer and fewer feminists to change oppressive laws; the starving self-help centers and mutual-aid networks; and, healthiest of all, the dazzling accomplishment of women’s art and scholarship. Nothing, it seems to me, is more exhilarating, and more dramatically to the point, than what is happening among the artists and scholars. The pejorative, limiting intention of the labels is still around (women playwrights, women photographers, etc., are obligatory annual roundups in various media) but not for long. It may be the first hint of a possible victory in being viewed and respected as human beings without being male-like or male dominated. Where self-sabotage is harder to maintain; where the worship of masculinity as a concept dies; where intelligent compassion for women unlike ourselves can surface; where racism and class inequity do not help the vision or the research; where, in fact, the work itself, the very process of doing it, makes sororicide as well as fratricide repulsive.

Thirty years after Miss Harriet Tubman—black, female, mother, daughter, nurse, cook, wife, and “commander of several men”—asked a roomful of sexist, bigoted, class-conscious white men for her back pay they g

ranted it. I have not chosen to begin and end this piece with her plea because it makes a poignant anecdote, but because the key to feminine oppression is most clearly seen in the response to her stand—a response that gathered together the full force of the special brand of American racism and sexism.

And don’t think she didn’t know it. They gave her twenty dollars a month for life. She was seventy-five years old then, and they probably did not expect the pension to have to last very long. Stubborn as a woman, she lived thirteen more years.

Literature and Public Life

To return to the site of one’s graduate school life, one is always in danger of repeating one’s original status in the place where inquiry occurs, problems surface, and help is needed to sort out all the difficulties so a clear and persuasive argument can be advanced. I feel like that now, lo, these many years later: perhaps a committee is sitting somewhere ready to interrogate me following their listening to this paper. It is a useful bit of recollection because I want to use this occasion and this provocative site to examine (or float) a few thoughts I have had no chance to articulate, except in my fiction. And to identify how those thoughts are made manifest in my work.

The problem I want to address this evening is, as I see it, the loss of public life, which is exacerbated by the degradation of private life. And I am proposing literature as an amelioration to this crisis in ways even literature could not have imagined.

Paradise

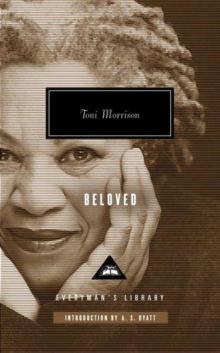

Paradise Beloved

Beloved Home

Home Tar Baby

Tar Baby The Bluest Eye

The Bluest Eye Jazz

Jazz Love

Love Sula

Sula Mouth Full of Blood

Mouth Full of Blood Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon The Source of Self-Regard

The Source of Self-Regard A Mercy

A Mercy Beloved_a novel

Beloved_a novel