- Home

- Toni Morrison

The Source of Self-Regard Page 25

The Source of Self-Regard Read online

Page 25

Three Lives centers on two immigrant women and one black woman who is never given a nationality, although she is the only natural-born citizen among the three. When a minor character in the Good Anna section visits Germany, her mother’s birthplace, and becomes embarrassed by Anna’s peasant manners, her remark is that her cousin is “no better than a nigger.” Miss Stein, fascinated with her project The Making of Americans has indeed delivered up to us a model case in literature: (1) build barriers in language and body, (2) establish difference in blood, skin, and human emotions, (3) place them in opposition to immigrants, and (4) voilà! The true American arises!

Sandwiched between a pair of immigrants—her aggression and power contained by the palms of chaste but restraining white women—Melanctha is bold but discredited; free to explore but bound by her color and confined by the white women on her left and her right, her foreground and her background, her beginning and her end, who precede her and follow her. The format and its interior workings say what is meant. All of the ingredients that have an impact on Americanness are on display in these women: labor, class, relations with the Old World, forging an un-European new culture, defining freedom, avoiding bondage, seeking opportunity and power, situating the uses of oppression. These considerations are inextricable from any deliberation on how Americans selected, chose, constructed a national identity. In the process of choosing, the unselected, the unchosen, the detritus is as significant as the cumulative, built American. Among the explorations vital to the definition, one of the strongest is the rumination of Africanistic character as a laboratory experiment for confronting emotional, historical, and moral problems as well as intellectual entanglements with the serious questions of power, privilege, freedom, and equity. Is it not just possible that the union, the coalescence of what America is and was made of, is incomplete without the place of Africanism in the formulation of this so-called new people, and what implications such a formulation had for the claims of democracy and egalitarianism as far as women and blacks were concerned? Is not the contradiction inherent in these two warring propositions—white democracy and black repression—also reflected in the literature so deeply that it marks and distinguishes its very heart?

Just as these two immigrants are literally joined like Siamese twins to Melanctha, so are Americans joined to and defined by this Africanistic presence at its spine.

Hard, True, and Lasting

“MANY STRANGERS TRAVERSE our land these days. They look on our lives with horror and quickly make means to pass on to the paradises of the north. Those who are pressed by circumstances and forced to tarry a while, grumble and complain endlessly. It is just good for them that we are inbred with habits of courtesy, hospitality, and kindness. It is good that they do not know the passion we feel for this parched earth. We tolerate strangers because the things we love cannot be touched by them.” That’s a paragraph from a short story called “The Green Tree” by Bessie Head, and I print all of it for you just to get to that one sentence: We tolerate strangers because the things we love cannot be touched by them. It suggests to me an attitude and a position that might be necessary for any artist and writer who finds himself not only in an alien culture, but vulnerable to it, and in some ways threatened by it.

There is nothing new or special about this condition of separateness—it is generally the first impression that an artist or a writer feels when he is compelled to write. And it may be even out of that feeling of separateness that he writes at all. The questions that all writers put are questions of value: identifying the values they feel worthy of preservation; or identifying the values they believe detrimental to some freer, or finer, or, at the least, steadier life.

Early national literatures all over the world concentrated on describing and, by implication, supporting the cultures that the writer found himself in. (The sagas, the lieder, the myths when they were recorded were precisely that.) Just as the early literature of expatriates, immigrants, or people in some form of diaspora concentrated on, and, frequently, condemned the new or alien culture the writers found themselves in. And the most assimilationist of them all brought something from his own culture to that assimilation. It is still rare to find massive flowerings of Joseph Conrads and Pushkins in national literature anthologies.

More recent literatures by both natives to and aliens in a culture are equally preoccupied with the problem. Indeed “alienation” became the password, the general catchall word for practically all post–World War II literature in the Western world. The writers view their own culture as alien: middle-class writers betrayed their own class and aspired toward the leisure-class values or the values of classes beneath them; working-class writers deplored the limitations of their own class; upper-class writers found inspiration among the poor, the “noble,” the innocent, the untutored peasant; postwar writers separated themselves from everybody except veterans and war victims. Of course there were and are writers who felt something quite the opposite: that things were pretty much all right the way they were and their suspicion of feeling alien came not from too little change, but too much, and too soon, which is to say before they were ready for it.

That the world is an exquisitely unpleasant place is a familiar ode to writers. And it is usually just at the point of reconciliation to the world, just at the moment when it becomes probably a comfortable enough place, after all that the writer is confronted with the Last Great Isolation—the one that minces every other alienation he has known: and that is the premonition of his own death. Under the shadow of that wing, even the most hostile of alien cultures is preferable.

But both of those conditions (my own awareness of being a native of this country and as an alien in it) are of interest to me as a writer, and I’d like to talk about that expected and perhaps inevitable sense of separateness from the culture that pervades the country I live in. The remarks I have to make are applicable to probably every group that has ever existed. And I paraphrase Miss Head to say that I can tolerate the overweening culture that is not mine because the things I love cannot be touched by it. It sounds hostile, I know, and unsharing, I know; and ungenerous and defensive. I know that. But I am nevertheless convinced that clarity about who one is and what one’s work is, is inextricably bound up with one’s place in a tribe—or a family, or a nation, or a race, or a sex, or what have you. And the clarity is necessary for the evaluation of the self and it is necessary for any productive intercourse with any other tribe or culture. I am not suggesting a collection of warring cultures, just clear ones, for it is out of the clarity of one’s own culture that life within another, near another, in juxtaposition to another is healthily possible. Without it, a writer lives on whatever pinnacle he achieves in loneliness and whatever road he walks on is finally a cul-de-sac. It is vital, therefore, to know what “the things we love” are, in order to care for and to husband them.

I have always myself felt most alive, most alert, and most sterling among my own people. All of my creative energy comes from there. My stimulation for any artistic effort at all originates there. The compulsion to write, even to be, begins with my consciousness of, experience with, and even my awe of black people and the quality of our lives as lived (not as perceived). And all of my instincts tell me that both as a writer and as a person any total surrender to another culture would destroy me. And the danger is not always from indifference; it is also from acceptance. It is sometimes called the fear of absorption, the horror of cultural embrace. But at the heart of the horror for me is what I know about what the history of the culture that pervades this country has been.

My instincts combine therefore with my intelligence to inform me that there are many aspects of that culture that are not trustworthy and are not supportive.

Every and each attempt I have made to write has centered on that assumption and this question: What is there of value in black culture to lose and how can it be preserved and made useful? I am not very good at the writing of tracts, so

I frequently identify the things I love and find of value by showing them in danger; things in my novels are threatened and sometimes destroyed. It is my way of directing attention at sensitized readers in such a way that they will yearn for, miss, and, I hope, learn to care for certain aspects of that life that are worth the preservation.

Now in order for me to try even to identify those things, I need to know a lot or try to find out a lot about the civilization within the civilization in which I grew up. I mean the black civilization that functioned within the white one. And the questions I must put to it are: What was the hierarchy in my civilization? Who were the arbiters of custom? What were the laws? Who were the outlaws—not the legal outlaws, but the community outlaws? Where did we go for solace and for advice? Who were the betrayers of that culture? Who did we respect and why? What was our morality? What was success? Who survived? And why? And under what circumstances? What is deviant behavior? Not deviant behavior as defined by white people, but what is deviant behavior as defined by black people?

I have been for years, and it will probably be a fascination that lasts all my life, continually fascinated by the fact that no bestial treatment of human beings ever produces beasts. White marauders can force Native American Indians to walk from one part of the country to another and watch them drop like flies and cattle, but they did not end up as cattle; Jewish people could be thrown into ovens like living carcasses but Jews were not bestialized by it; black people could be enslaved for generation after generation and recorded in statistics along with lists of rice, tar, and turpentine cargo, but they did not turn out to be cargo. Each one of those groups civilized the very horror that oppressed it. It doesn’t work, and I don’t think it can. It never works; what preoccupies me is why. Why was the quality of my great-grandmother’s life so much better than the circumstances of her life? How was it possible without the feminist movement, without a black arts movement, without any movement, how was it possible that the sheer integrity and quality of her life were so superior to its circumstances? I know that she was not atypical among the women of her day. She was as average a black woman as there ever was. And no amount of quisling scholarship, no amount of psychological tyranny, no number of black colonizers, who in their quest for jobs and national prominence join hands with those who would rape us culturally, none of them will ever convince me otherwise. Because I knew her—and I knew the people she knew.

In my own writing, in order to reveal what seems to me the hard and the true and the lasting things, I am drawn to describing people under duress, not in easy circumstances, but backed up into a corner, people called upon to fish or cut bait. You say you are my friend? Let’s see. You say you are a revolutionary? Let me see how it looks when I push you all the way out. You say you love me? Let’s see. What happens if you follow your course all the way through? What are the things you will give up? And, under duress, I know who they are, of what they are made, and which of their qualities is the last to go, and which of their qualities never go. It gives a melancholy cast to my work. I know. And it leads me to exceptional rather than routine characters. I know. And it leaves me wide open for criticism about bizarre characters and nonpositive images. I know. But I am afraid I will have to leave the “positive” images to the comic-strip artists and the “normal” black characters to some future Doris Day, because I believe it is silly, not to say irresponsible, to concern myself with lipstick and Band-Aid when there is a plague in the land. The so-called everyday life of black people is certainly lovely to live, but whoever is living it must know that each day of his “everyday” black life is a triumph of matter over mind and sentiment over common sense. And if he doesn’t know that, then he doesn’t know anything at all. As the young African poet Keorapetse Kgositsile put it, “The present is a dangerous place to live.” Superficial literary cosmetics will not save us from that danger. As a matter of fact, literature will not save us at all. All it can do is point out the need perhaps for defense, but it is not itself that defense. What it can do is participate in the process of identifying what is of value, and once that surfaces, once black tradition can be extricated from black fashion, once black writing stops posturing and catering to the voyeurs of black life, once it stops doing an American version of airport art, then an even harder job presents itself.

Because it is relatively easy to recognize values in isolation. The problem gets complicated when those values are in conflict with other values. For then you have to figure out how to protect the very best of the group sensibilities; how to protect the noblest impulses. What are the nurturing structures worth keeping in the community? What are the culturgens that provide emotional safety, the customs that allow freedom without excessive risk or certain destruction, that allow courage minus recklessness, generosity without waste, support without domination, and in times of deep, deep trouble (as in some of the black countries abroad) a resource for survival that may very well include sustained and calculated ferocity.

Black writers who are committed to the renewal and refreshment of values can be identified by their taste, by their judgments, by their intellect, and by their work. They do not use black life as exotic ornament for pedestrian nonblack stories. The essence of black life is the substance, not the decoration, of their work. Their work turns on a moral axis that has been forged among black people. They do not impose alien moralities about broken homes, and house-bound fathers, and petite power, and what is or is not gainful employment on their characters.

They do not regard black language as dropping g’s or as an exercise in questionable phonetics and inconsistent orthography. They know that it is much more complicated than that.

And they waste no time explaining, explaining, explaining away everything they feel and think and do—to the other culture. They are challenged by and concerned with the enlightenment of their own, even when the enlightenment includes painful information.

They do not view the habits and customs of their people with the eye of a charged-up ethnologist examining curios.

The writers who are also scholars in so-called black studies are unimpressed with standard cries of “lowering standards” when any change in curricula is recommended. They know their job doesn’t have anything to do with maintaining standards. It has to do with reshaping the content of those standards in order to improve them and raise them.

Those black writers who are critics are not busy painting Bertolt Brecht black and relabeling his thoughts (which were perfectly suitable to his own cultural needs) as some sort of “new” black criticism. Any critical apparatus or critical system that is inappropriate to and foolish when applied to black music or non-Western black art is fraudulent when applied to black literature.

Once, when I first began to write, I didn’t know a lot about how to dramatize and I was forced sometimes to use exposition as a way of saying something I could not properly show. And in the first book, The Bluest Eye, I wrote a passage at the end that is as close as I have ever gotten to sustained didacticism. It is a wholly unsatisfactory passage to me, and I had certainly hoped to read it to you in context, but I haven’t got a copy of the book with me. But in the last two pages of The Bluest Eye, is, in essence, what I believe to be the dangers when one assumes that you can substitute license for freedom, when one assumes that you can use another’s deficiency for one’s own generosity, when one assumes that you can use another person’s misery and nightmares in order to clarify your own dreams. When all of those things are done and completed, then the surrender and the betrayal of one’s culture is also complete.

PART II

God’s Language

James Baldwin Eulogy

Jimmy, there is too much to think about you, and much too much to feel. The difficulty is your life refuses summation—it always did—and invites contemplation instead. Like many of us left here, I thought I knew you. Now I discover that, in your company, it is myself I know. That is the astonishing gift of your art and your

friendship: you gave us ourselves to think about, to cherish. We are like Hall Montana watching “with a new wonder” his brother sing, knowing the song he sang is us, “he is—us.”

I never heard a single command from you, yet the demands you made on me, the challenges you issued to me were nevertheless unmistakable if unenforced: that I work and think at the top of my form; that I stand on moral ground but know that ground must be shored up by mercy; that “the world is before [me] and [I] need not take it or leave it as it was when [I] came in.”

Well, the season was always Christmas with you there, and like one aspect of that scenario, you did not neglect to bring at least three gifts. You gave me a language to dwell in—a gift so perfect, it seems my own invention. I have been thinking your spoken and written thoughts so long, I believed they were mine. I have been seeing the world through your eyes so long, I believed that clear, clear view was my own. Even now, even here, I need you to tell me what I am feeling and how to articulate it. So I have pored (again) through the 6,895 pages of your published work to acknowledge the debt and thank you for the credit.

No one possessed or inhabited language for me the way you did. You made American English honest—genuinely international. You exposed its secrets and reshaped it until it was truly modern, dialogic, representative, humane. You stripped it of ease and false comfort and fake innocence and evasion and hypocrisy. And in place of deviousness was clarity; in place of soft, plump lies was a lean, targeted power. In place of intellectual disingenuousness and what you called “exasperating egocentricity,” you gave us undecorated truth. You replaced lumbering platitudes with an upright elegance. You went into that forbidden territory and decolonized it, “robbed it of the jewel of its naïveté,” and ungated it for black people, so that in your wake we could enter it, occupy it, restructure it in order to accommodate our complicated passion. Not our vanities, but our intricate, difficult, demanding beauty; our tragic, insistent knowledge; our lived reality; our sleek classical imagination. All the while refusing “to be defined by a language that has never been able to recognize [us].” In your hands language was handsome again. In your hands we saw how it was meant to be—neither bloodless nor bloody, and yet alive.

Paradise

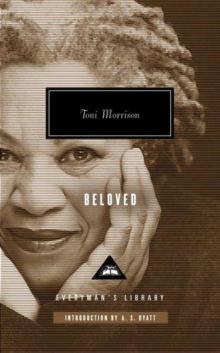

Paradise Beloved

Beloved Home

Home Tar Baby

Tar Baby The Bluest Eye

The Bluest Eye Jazz

Jazz Love

Love Sula

Sula Mouth Full of Blood

Mouth Full of Blood Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon The Source of Self-Regard

The Source of Self-Regard A Mercy

A Mercy Beloved_a novel

Beloved_a novel