- Home

- Toni Morrison

A Mercy Page 8

A Mercy Read online

Page 8

Rebekka doubted that she would be infected. None of her parents’ relatives had died during the pestilence; they boasted that no red cross had been painted on their door, although they saw hundreds and hundreds of dogs slaughtered and cartloads of the dead creaking by the commons. So to have sailed to this clean world, this fresh and new England, marry a stout, robust man and then, on the heels of his death, to lie festering on a perfect spring night felt like a jest. Congratulations, Satan. That was what the cutpurse used to say whenever the ship rose and threw their bodies helter-skelter.

“Blasphemy!” Elizabeth would shout.

“Truth!” Dorothea replied.

Now they hovered in the doorway or knelt by her bed.

“I’m already dead,” said Judith. “It’s not so bad.”

“Don’t tell her that. It’s horrid.”

“Don’t listen to her. She’s a pastor’s wife now.”

“Would you like some tea?”

“I married a sailor, so I’m always alone.”

“She supplements his earnings. Ask her how.”

“There are laws against that.”

“Surely, but they would not have them if they did not need them.”

“Listen, let me tell you what happened to me. I met this man.…”

Just as on the ship, their voices knocked against one another. They had come to soothe her but, like all ghostly presences, they were interested only in themselves. Yet the stories they told, their comments, offered Rebekka the distraction of other people’s lives. Well, she thought, that was the true value of Job’s comforters. He lay wracked with pain and in moral despair; they told him about themselves, and when he felt even worse, he got an answer from God saying, Who on earth do you think you are? Question me? Let me give you a hint of who I am and what I know. For a moment Job must have longed for the self-interested musings of humans as vulnerable and misguided as he was. But a peek into Divine knowledge was less important than gaining, at last, the Lord’s attention. Which, Rebekka concluded, was all Job ever wanted. Not proof of His existence—he never questioned that. Nor proof of His power—everyone accepted that. He wanted simply to catch His eye. To be recognized not as worthy or worthless, but to be noticed as a life-form by the One who made and unmade it. Not a bargain; merely a glow of the miraculous.

But then Job was a man. Invisibility was intolerable to men. What complaint would a female Job dare to put forth? And if, having done so, and He deigned to remind her of how weak and ignorant she was, where was the news in that? What shocked Job into humility and renewed fidelity was the message a female Job would have known and heard every minute of her life. No. Better false comfort than none, thought Rebekka, and listened carefully to her shipmates.

“He knifed me, blood everywhere. I grabbed my waist and thought, No! No swooning, my girl. Steady.…”

When the women faded, it was the moon that stared back like a worried friend in a sky the texture of a fine lady’s ball gown. Lina snored lightly on the floor at the foot of the bed. At some point, long before Jacob’s death, the wide untrammeled space that once thrilled her became vacancy. A commanding and oppressive absence. She learned the intricacy of loneliness: the horror of color, the roar of soundlessness and the menace of familiar objects lying still. When Jacob was away. When neither Patrician nor Lina was enough. When the local Baptists tired her out with talk that never extended beyond their fences unless it went all the way to heaven. Those women seemed flat to her, convinced they were innocent and therefore free; safe because churched; tough because still alive. A new people remade in vessels old as time. Children, in other words, without the joy or the curiosity of a child. They had even narrower definitions of God’s preferences than her parents. Other than themselves (and those of their kind who agreed), no one was saved. The possibility was open to most, however, except children of Ham. In addition there were Papists and the tribes of Judah to whom redemption was denied along with a variety of others living willfully in error. Dismissing these exclusions as the familiar restrictions of all religions, Rebekka held a more personal grudge against them. Their children. Each time one of hers died, she told herself it was anti-baptism that enraged her. But the truth was she could not bear to be around their undead, healthy children. More than envy she felt that each laughing red-cheeked child of theirs was an accusation of failure, a mockery of her own. Anyway, they were poor company and of no help to her with the solitude without prelude that could rise up and take her prisoner when Jacob was away. She might be bending in a patch of radishes, tossing weeds with the skill of a pub matron dropping coins into her apron. Weeds for the stock. Then as she stood in molten sunlight, pulling the corners of her apron together, the comfortable sounds of the farm would drop. Silence would fall like snow floating around her head and shoulders, spreading outward to wind-driven yet quiet leaves, dangling cowbells, the whack of Lina’s axe chopping firewood nearby. Her skin would flush, then chill. Sound would return eventually, but the loneliness might remain for days. Until, in the middle of it, he would ride up shouting,

“Where’s my star?”

“Here in the north,” she’d reply and he would toss a bolt of calico at her feet or hand her a packet of needles. Best of all were the times when he would take out his pipe and embarrass the songbirds who believed they owned twilight. A still living baby would be on her lap. Patrician would be on the floor, mouth agape, eyes aglow, as he summoned rose gardens and shepherds neither had seen or would ever know. With him, the cost of a solitary, unchurched life was not high.

Once, feeling fat with contentment, she curbed her generosity, her sense of excessive well-being, enough to pity Lina.

“You have never known a man, have you?”

They were sitting in the brook, Lina holding the baby, splashing his back to hear him laugh. In frying August heat they had taken the washing down to a part of the brook that swarming flies and vicious mosquitoes ignored. Unless a light canoe sailed by very close to the riverbank beyond no one would see them. Patrician knelt nearby watching how her bloomers stirred in the ripples. Rebekka sat in her underwear rinsing her neck and arms. Lina, naked as the baby she held in her arms, lifted him up and down watching his hair reshape itself in the current. Then she held him over her shoulder and sent cascades of clear water over his back.

“Known, Miss?”

“You understand me, Lina.”

“I do.”

“Well?”

“Look,” squealed Patrician, pointing.

“Shhh,” Lina whispered. “You will frighten them.” Too late. The vixen and her kits sped away to drink elsewhere.

“Well?” Rebekka repeated. “Have you?”

“Once.”

“And?”

“Not good. Not good, Miss.”

“Why was that?”

“I will walk behind. I will clean up after. I will not be thrashed. No.”

Handing the baby to his mother, Lina stood and walked to the raspberry bushes where her shift hung. Dressed, she cradled the laundry basket in her arm and held out a hand to Patrician.

Left alone with the baby who more than any of her children favored their father, Rebekka savored again on that day the miracle of her good fortune. Wife beating was common, she knew, but the restrictions—not after nine at night, with cause and not anger—were for wives and only wives. Had he been a native, Lina’s lover? Probably not. A rich man? Or a common soldier or sailor? Rebekka suspected the rich man since she had known kind sailors but, based on her short employment as a kitchen maid, had seen only the underside of gentry. Other than her mother, no one had ever struck her. Fourteen years and she still didn’t know if her mum was alive. She once received a message from a captain Jacob knew. Eighteen months after he was charged to make inquiries, he reported that her family had moved. Where, no one could say. Rising from the brook, laying her son in the warm grass while she dressed, Rebekka had wondered what her mother might look like now. Gray, stooped, wrinkled? Would the sharp pale eye

s still radiate the shrewdness, the suspicion, Rebekka hated? Or maybe age, illness, had softened her to benign, toothless malice.

Confined to bed now, her question was redirected. “And me? How do I look? What lies in my eyes now? Skull and crossbones? Rage? Surrender?” All at once she wanted it—the mirror Jacob had given her which she had silently rewrapped and tucked in her press. It took a while to convince her, but when Lina finally understood and fixed it between her palms, Rebekka winced.

“Sorry,” she murmured. “I’m so sorry.” Her eyebrows were a memory, the pale rose of her cheeks collected now into buds of flame red. She traveled her face slowly, gently apologizing. “Eyes, dear eyes, forgive me. Nose, poor mouth. Poor, sweet mouth, I’m sorry. Believe me, skin, I do apologize. Please. Forgive me.”

Lina, unable to pry the mirror away, was pleading with her.

“Miss. Enough. Enough.”

Rebekka refused and clung to the mirror.

Oh, she had been so happy. So hale. Jacob home and busy with plans for the new house. The evenings when he was exhausted and she picked his hair clean; the mornings when she tied it. She loved his voracious appetite and the pride he took in her cooking. The blacksmith, who worried everybody except herself and Jacob, was like an anchor holding the couple in place in untrustworthy waters. Lina was afraid of him. Sorrow grateful as a hound to him. And Florens, poor Florens, she was completely smitten. Of the three, only she could be counted on to get to him. Lina would have begged off, unwilling to leave her patient, of course, but, more than that, despising him. Pregnant stupid Sorrow could not have. Rebekka had confidence in Florens because she was clever and because she had a strong reason to succeed. And she felt a lot of affection for her, although it took some time to develop. Jacob probably believed giving her a girl close to Patrician’s age would please her. In fact, it insulted her. Nothing could replace the original and nothing should. So she barely glanced at her when she came and had no need to later because Lina took the child so completely under her wing. In time, Rebekka thawed, relaxed, was even amused by Florens’ eagerness for approval. “Well done.” “It’s fine.” However slight, any kindness shown her she munched like a rabbit. Jacob said the mother had no use for her which, Rebekka decided, explained her need to please. Explained also her attachment to the blacksmith, trotting up to him for any reason, panicked to get his food to him on time. Jacob dismissed Lina’s glower and Florens’ shine: the blacksmith would soon be gone, he said. No need to worry, besides the man was too skilled and valuable to let go, certainly not because a girl was mooning over him. Jacob was right, of course. The smithy’s value was without price when he cured Sorrow of whatever had struck her down. Pray to God he could repeat that miracle. Pray also Florens could persuade him. They’d stuffed her feet in good strong boots. Jacob’s. And folded a clarifying letter of authority inside. And her traveling instructions were clear.

It would all be all right. Just as the pall of childlessness coupled with bouts of loneliness had disappeared, melted like the snow showers that signaled it. Just as Jacob’s determination to rise up in the world had ceased to trouble her. She decided that the satisfaction of having more and more was not greed, was not in the things themselves, but in the pleasure of the process. Whatever the truth, however driven he seemed, Jacob was there. With her. Breathing next to her in bed. Reaching for her even as he slept. Then suddenly, he was not.

Were the Anabaptists right? Was happiness Satan’s allure, his tantalizing deceit? Was her devotion so frail it was merely bait? Her stubborn self-sufficiency outright blasphemy? Is that why at the height of her contentedness, once again death turned to look her way? And smile? Well, her shipmates, it seemed, had got on with it. As she knew from their visits, whatever life threw up, whatever obstacles they faced, they manipulated the circumstances to their advantage and trusted their own imagination. The Baptist women trusted elsewhere. Unlike her shipmates, they neither dared nor stood up to the fickleness of life. On the contrary, they dared death. Dared it to erase them, to pretend this earthly life was all; that beyond it was nothing; that there was no acknowledgment of suffering and certainly no reward; they refused meaninglessness and the random. What excited and challenged her shipmates horrified the churched women and each set believed the other deeply, dangerously flawed. Although they had nothing in common with the views of each other, they had everything in common with one thing: the promise and threat of men. Here, they agreed, was where security and risk lay. And both had come to terms. Some, like Lina, who had experienced both deliverance and destruction at their hands, withdrew. Some, like Sorrow, who apparently was never coached by other females, became their play. Some like her shipmates fought them. Others, the pious, obeyed them. And a few, like herself, after a mutually loving relationship, became like children when the man was gone. Without the status or shoulder of a man, without the support of family or well-wishers, a widow was in practice illegal. But was that not the way it should be? Adam first, Eve next, and also, confused about her role, the first outlaw?

The Anabaptists were not confused about any of this. Adam (like Jacob) was a good man but (unlike Jacob) he had been goaded and undermined by his mate. They understood, also, that there were lines of acceptable behavior and righteous thought. Levels of sin, in other words, and lesser peoples. Natives and Africans, for instance, had access to grace but not to heaven—a heaven they knew as intimately as they knew their own gardens. Afterlife was more than Divine; it was thrill-soaked. Not a blue and gold paradise of twenty-four-hour praise song, but an adventurous real life, where all choices were perfect and perfectly executed. How had the churchwoman she spoke to described it? There would be music and feasts; picnics and hayrides. Frolicking. Dreams come true. And perhaps if one was truly committed, consistently devout, God would take pity and allow her children, though too young for a baptism of full immersion, entrance to His sphere. But of greatest importance, there was time. All of it. Time to converse with the saved, laugh with them. Skate, even, on icy ponds with a crackling fire ashore to warm one’s hands. Sleighs jingled and children made snow houses and played with hoops in the meadow because the weather would be whatever you wanted it to be. Think of it. Just imagine. No illness. Ever. No pain. No aging or frailty of any kind. No loss or grief or tears. And obviously no more dying, not even if the stars shattered into motes and the moon disintegrated like a corpse beneath the sea.

She had only to stop thinking and believe. The dry tongue in Rebekka’s mouth behaved like a small animal that had lost its way. And though she understood that her thoughts were disorganized, she was also convinced of their clarity. That she and Jacob could once talk and argue about these things made his loss intolerable. Whatever his mood or disposition, he had been the true meaning of mate.

Now, she thought, there is no one except servants. The best husband gone and buried by the women he left behind; children rose-tinted clouds in the sky. Sorrow frightened for her own future if I die, as she should be, a slow-witted girl warped from living on a ghost ship. Only Lina was steady, unmoved by any catastrophe as though she has seen and survived everything. As in that second year when Jacob was away, caught in an off-season blizzard, and she, Lina and Patrician after two days were close to starvation. No trail or road passable. Patrician turning blue in spite of the miserable dung fire sputtering in a hole in the dirt floor. It was Lina who dressed herself in hides, carried a basket and an axe, braved the thigh-high drifts, the mind-numbing wind, to get to the river. There she pulled from below the ice enough broken salmon to bring back and feed them. She filled her basket with all she could snare; tied the basket handle to her braid to keep her hands from freezing on the trek back.

That was Lina. Or was it God? Here in an abyss of loss, she wondered if the journey to this land, the dying off of her family, her whole life, in fact, were way-stations marking a road to revelation. Or perdition? How would she know? And now with death’s lips calling her name, to whom should she turn? A blacksmith? Florens?

&

nbsp; How long will it take will he be there will she get lost will someone assault her will she return will he and is it already too late? For salvation.

I sleep then wake to any sound. Then I am dreaming cherry trees walking toward me. I know it is dreaming because they are full in leaves and fruit. I don’t know what they want. To look? To touch? One bends down and I wake with a little scream in my mouth. Nothing is different. The trees are not heavy with cherries nor nearer to me. I quiet down. That is a better dream than a minha mãe standing near with her little boy. In those dreams she is always wanting to tell me something. Is stretching her eyes. Is working her mouth. I look away from her. My next sleeping is deep.

Not birdsong but sunlight wakes me. All snow is gone. Relieving myself is troublesome. Then I am going north I think but maybe west also. No, north until I come to where the brush does not let me through without clutching me and taking hold. Brambles spread among saplings are wide and tall to my waist. I press through and through for a long time which is good since in front of me sudden is an open meadow wild with sunshine and smelling of fire. This is a place that remembers the burning of itself. New grass is underfoot, deep, thick, tender as lamb’s wool. I stoop to touch it and remember how Lina loves to unravel my hair. It makes her laugh, saying it is proof I am in truth a lamb. And you, I ask her. A horse she answers and tosses her mane. It is hours I walk this sunny field, my thirst so loud I am faint. Beyond I see a light wood of birch and apple trees. The shade in there is green with young leaves. Bird talk is everyplace. I am eager to enter because water may be there. I stop. I hear hoofbeats. From among the trees riders clop toward me. All male, all native, all young. Some look younger than me. None have saddles on their horses. None. I marvel at that and the glare of their skin but I have fear of them too. They rein in close. They circle. They smile. I am shaking. They wear soft shoes but their horses are not shod and the hair of both boys and horses is long and free like Lina’s. They talk words I don’t know and laugh. One pokes his fingers in his mouth, in out, in out. Others laugh more. Him too. Then he lifts his head high, opens wide his mouth and directs his thumb to his lips. I drop to my knees in misery and fright. He dismounts and comes close. I smell the perfume of his hair. His eyes are slant, not big and round like Lina’s. He grins while removing a pouch hanging from a cord across his chest. He holds it out to me but I am too trembling to reach so he drinks from it and offers it again. I want it am dying for it but I cannot move. What I am able to do is make my mouth wide. He steps closer and pours the water as I gulp it. One of the others says baa baa baa like a goat kid and they all laugh and slap their legs. The one pouring closes his pouch and after watching me wipe my chin returns it to his shoulder. Then he reaches into a belt hanging from his waist and draws out a dark strip, hands it to me, chomping his teeth. It looks like leather but I take it. As soon as I do he runs and leaps on his horse. I am shock. Can you believe this. He runs on grass and flies up to sit astride his horse. I blink and they all disappear. Where they once are is nothing. Only apple trees aching to bud and an echo of laughing boys.

Paradise

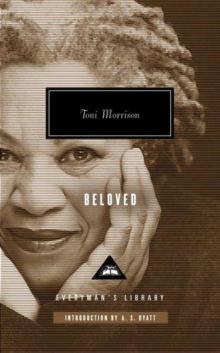

Paradise Beloved

Beloved Home

Home Tar Baby

Tar Baby The Bluest Eye

The Bluest Eye Jazz

Jazz Love

Love Sula

Sula Mouth Full of Blood

Mouth Full of Blood Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon The Source of Self-Regard

The Source of Self-Regard A Mercy

A Mercy Beloved_a novel

Beloved_a novel